BONUS: Interview with Author Ina Cole, "From the Sculptor's Studio"

Hello, ArtCurious folks! I have a special treat for you today: a written interview with author Ina Cole, regarding her recent book, From the Sculptor’s Studio: Conversations with Twenty Seminal Artists. Ina and I wanted to do this as a traditional audio interview or Fireside chat, but ultimately decided to go old-school— which makes this a wonderful ArtCurious first! I very much enjoyed her answers to my questions—which helps us understand the processes of contemporary British sculpture artists. Being a curator of contemporary art myself, I’ve long celebrated one of the benefits of working with contemporary artists: being able to speak with them, pick their brains, ask them to fully describe their works (as much as I’d like to do the same with Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun, unfortunately that’s not possible!). Please enjoy the following conversation with Ina Cole, and seek out From the Sculptor’s Studio wherever you can.

Ina Cole has written widely on twentieth-century and contemporary art, publishing articles, artist interviews, essays and exhibition catalogs. She is the UK contributing editor for ‘Sculpture’; a journal affiliated to the International Sculpture Center in the US. Following ten years at Tate St Ives and the Barbara Hepworth Museum, she held several positions within culture and higher education, and has facilitated many live debates with artists. Ina has an MA in the History of Modern Art and Design from Falmouth University, Cornwall. She also has an interest in typographic design and photography, and holds a collection of historically important graphic works, as well as an archive of black & white photographs and negatives from the mid twentieth-century onward.

“I wanted the publication to feel celebratory, as well as reinforce Britain’s reputation as a leading force within sculptural practice worldwide.”

What inspired you to write the book?

When doing my research, I noticed there are relatively few books on sculpture where the maker’s ideas are fully articulated in their own words. Instead, there’s a tendency to place sculptors with international peers who often work in medium other than sculpture, or texts are laden with author opinion. This inspired me to write a book about sculptors practicing in Britain, but with texts based on recorded conversations. Although the artists situate themselves in Britain, mainly London, their work is exhibited internationally. So I wanted the publication to feel celebratory, as well as reinforce Britain’s reputation as a leading force within sculptural practice worldwide.

Can you tell me a little about how you selected the artists to feature? Is there one conversation in particular that impacted the way you approach art?

The featured artists have all made a decisive contribution to the lineage of British sculpture, and that was a key factor in my selection. My aim was to build upon Britain’s sculptural legacy, from its Modernist roots in the 1930s, through to these contemporary acts of making. It’s hard to pick just one conversation though, as all the artists have much to teach us when it comes to approaching art. However, I was fascinated by David Nash’s description of Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals, and the way they impacted on the making of his sculpture, Two Ubus. Nash first saw the Seagram Murals at age 21, but on revisiting them years later he was struck by how different they appeared. An artwork doesn’t change as such, yet it’s important that you can allow your interpretation of it to evolve.

In your introduction, you mention how “process is, in itself, an adventure, through which new discoveries are realized.” What was one of the most inspiring or illuminating discoveries you heard while interviewing these artists?

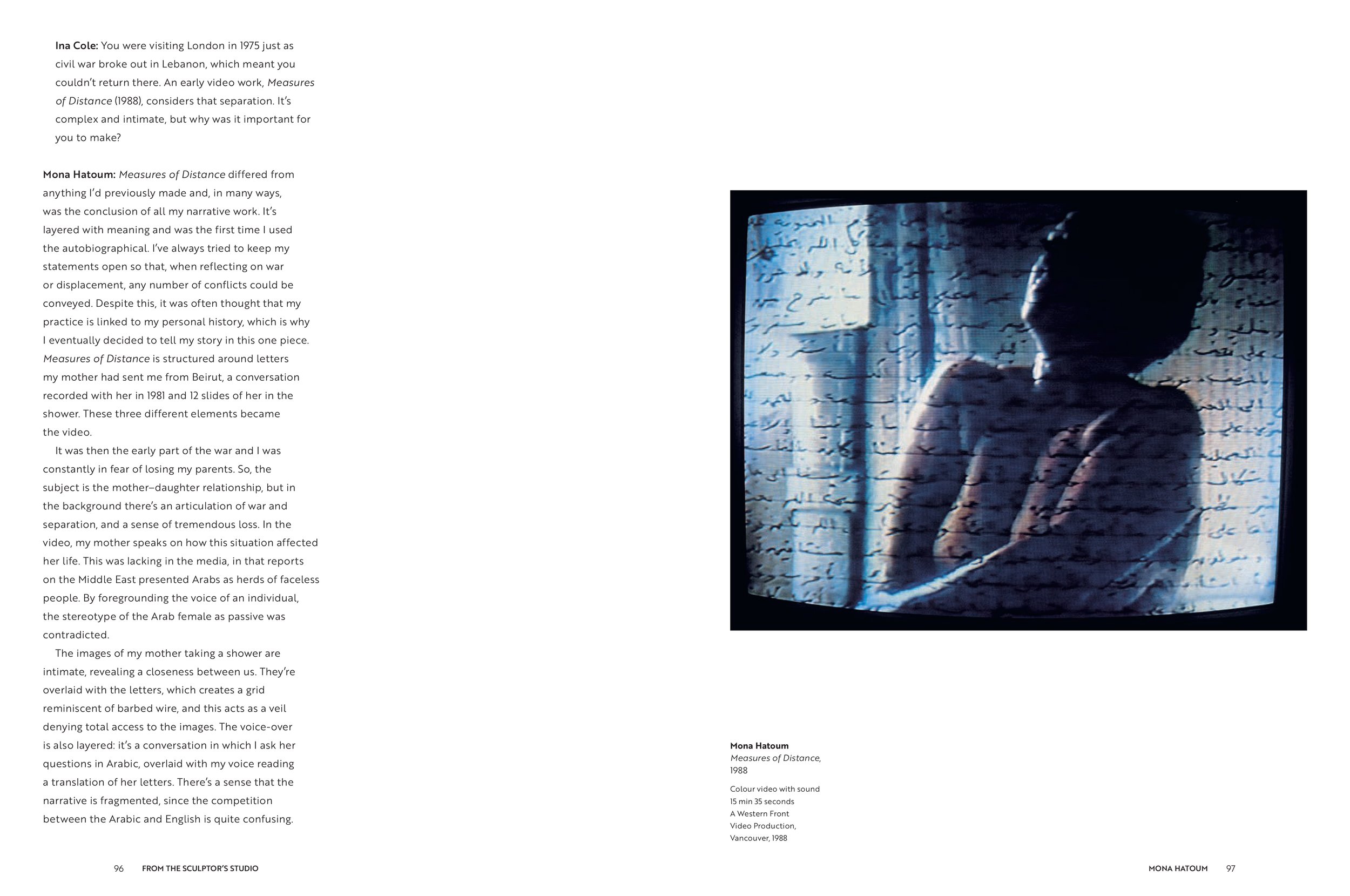

I made many illuminating discoveries. Again, it’s quite difficult to highlight one in particular. A few, however, I can immediately bring to mind: Phyllida Barlow, a great-great grandchild of Charles Darwin, talking about his impact on her family life; Anthony Caro and the challenges of working on his commission for the church of Saint-Jean-Baptiste; Antony Gormley detailing the process he undertook when installing ‘Sight’ on the island of Delos; and Mona Hatoum’s moving account of how separation from her family inspired the making of Measures of Distance. There are 20 artists in the book, and my intention at the outset was to develop in-depth interviews where they reveal how their most notable artworks came into being. So the publication naturally contains many intriguing back stories.

What was the first sculpture that resonated with you, that made you stop in your tracks and absorb every inch of its detail?

I was introduced to sculpture by my parents, when I was still at school. We went on holiday to St Ives in Cornwall, UK, to visit the Barbara Hepworth Museum. I recall my mother ushering me towards one of Hepworth’s unfinished sculptures, sited in a greenhouse full of exotic cacti. Although the artist had long passed, her presence seemed almost tangible. The informality of the space – and the way light streamed through the glass to animate the sculpture – seemed magical to me. Serendipitously, years later I was recruited for the opening of Tate St Ives, to which the Hepworth Museum is affiliated. So, I was able to relive that treasured early experience on a daily basis.

Cornelia Parker, Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View, 1991. Blown-up garden shed and contents, wire, light bulb. Dimensions variable. Installation view: Chisenhale Gallery, London, 1991.

Relatedly, which sculptures from the artists you interviewed have you seen in person and absolutely took your breath away? I’m guessing Cornelia Parker’s Cold Dark Matter was one of them – the pieces of a blown-up garden shed hanging in mid-air would be incredible to see live!

I’ve seen many of the sculptures in person but, yes, Cold Dark Matter is an unforgettable work. In making it, a garden shed was first blown up by British Army personnel, then its blackened remains were suspended. Through this act of destruction, then reconstruction, Parker has recreated the explosion, held in mid-air. The shed’s vestiges are lit by a central light bulb, thereby casting the most extraordinary shadows. I found it completely mesmerizing. Susan Hiller’s Witness is similarly immersive. Here, you step into an otherworldly environment which, to me, felt quite oceanic. A continual murmuring can be heard, channeled through 350 suspended speakers. On drawing close and holding the speakers to your ear, you hear voices recalling personal stories of alien encounters from across the globe. You feel as if you’re part of the ensemble, or complicit in some way, which is a significant feature of Hiller’s work.

Susan Hiller, Witness, 2000. Audio-sculpture: 350 speakers suspended from ceiling, 10 audio tracks, switching equipment, steel structure, amplifiers, wiring, lights. Size: approx. 1800 °— 900 cm (59 °— 30 ft) Installation view: Artangel at The Chapel, London, 2000.

Marc Quinn, Self, 1991. Blood (the artist's), stainless steel, Perspex and refrigeration equipment. 208 °— 63 °— 63 cm (6 ft 97∕8 in °— 24. in °— 24. in)

One of the more macabre pieces featured is Marc Quinn’s Self – a cast of the artist’s head made from 10 pints of his own blood and immersed in frozen silicone. In your interview with Quinn, he mentioned wanting to bring “real life into art.” With the age of AI realism and media that shows more and more graphic footage every day, how will artists like Marc Quinn – who quite literally pour blood, sweat and tears into their work – continue to make their art feel vibrant and alive?

Quinn’s practice often encourages social interaction and debate and, by doing so, it brings real life into art. He actually told me he didn’t want to make ‘selfs’ of other people, but produce something with a collective, which he’s achieved with two new works, 100 Heads and Our Blood. 100 Heads are concrete portrait busts of a cross-section of the global refugee population. The refugee crisis is, of course, one of the most pertinent issues of our time.100 Heads is a precursor to Our Blood, which premieres at New York Public Library in 2022. This public artwork consists of two identical cubes of frozen human blood, displayed in refrigeration units. One cube is made from blood donated by refugee volunteers, the other by non-refugees – over 10,000 volunteers in total. After premiering, it will tour the world to keep this debate alive. Blood is the most essential element and unites humankind. So the discussion generated by Our Blood as it travels becomes part its story, as much as the materials it’s made from.

“...An artwork has to go out into the world and assume a life of its own. [And] the perception others bring to it can be enriching, even if their observations are not as the artist intended. ”

What would you say to young artists who are worried that once their work leaves the studio it won’t be perceived in the way they originally intended?

I think this is inevitable, so I’d say, don’t dwell and move onto your next project. However, I wrote the book in order to capture the voice of the artist, as I’m fully aware of how passing time distorts artistic intention. Creative motivation can become manipulated, politicized, and neutralized by the shifting zeitgeist. It’s an irresolvable paradox. Still, an artwork has to go out into the world and assume a life of its own. And, the perception others bring to it can be enriching, even if their observations are not as the artist intended.

What do you hope the reader will learn or gain from the book?

Well, each conversation goes behind the scenes, into the studio, to reveal how artworks and exhibitions are created. So I hope the book offers readers an enlightening experience. Images of the artworks are aligned with the text, which really helps to open up the world of sculpture. I think it’s an indispensable publication for art students, curators and collectors yet, equally, can be enjoyed by those with a more informal interest in art. It’s also a useful tool for researchers looking to cite contemporary artists, as it contains such extensive primary research.

Interior spread from From the Sculptor’s Studio, featuring Mona Hatoum, Measures of Distance, 1988. Color video with sound. 15 min 35 seconds. A Western Front Video Production, Vancouver, 1988

What were some of your takeaways after interviewing each artist and writing this book? What advice might you have received that you can share with fellow artists?

I think clarity of focus, and a dose of single-mindedness, are important attributes for anyone embarking on an artistic career. As is the ability to question the status quo, even when the odds seemed stacked against you. Phyllida Barlow illustrates this point well with an early piece, Tent, which was a complete break from her previous work. Despite the fact it provoked hostility, and was never exhibited, she trusted her instincts. Richard Long battles the pouring rain, freezing cold, blizzards and sandstorms to produce often transitory artworks. Rachel Whiteread encountered emotional and political turmoil when constructing House and Holocaust Memorial. And, when making Slipstream, a Heathrow airport commission, Richard Wilson had to transport all its sections over 22 journeys with a police escort. Challenges are both physical and cerebral, often simultaneously. A creative life is not for the faint hearted. Yet, the rewards are invaluable for those who persevere.

Thanks to Ina Cole for her compelling interview and for From the Sculptor’s Studio! Special thanks, too, to Laurence King Publishing and to Tayla Monturio for arranging this conversation.